Friends outside Puerto Rico frequently ask me for post-Maria Puerto Rico updates, which is perfectly logical. I do live here, after all, and publish a blog called The Resilience Journal. The usual conversation starts out: “How’s it going?” “Much better.” “What’s being done to make the island resilient next time?” “Not much yet. Still a work in progress.” Finally: “You should do a post with an update.” To which I usually answer: “Good idea.”

I was, in fact, about to do one at the 3/20 mark, six months after 9/20 Maria. But wait a minute, I said. Yet another update on what’s happening is not, I believe, what is needed. There have been so many, and more come out constantly. Really outstanding reporters visit the island just about every week and file excellent stories. For a sampling, see here, here, here. and do this search.

TRJ’s value, instead, is in bringing you the angle you are not reading elsewhere. In the case of this dramatic story, we figure that means not a follow-up, but rather a series of special reports that make a difference by going where others do not: toward a resilient future, no less. This column is meant to set the table.

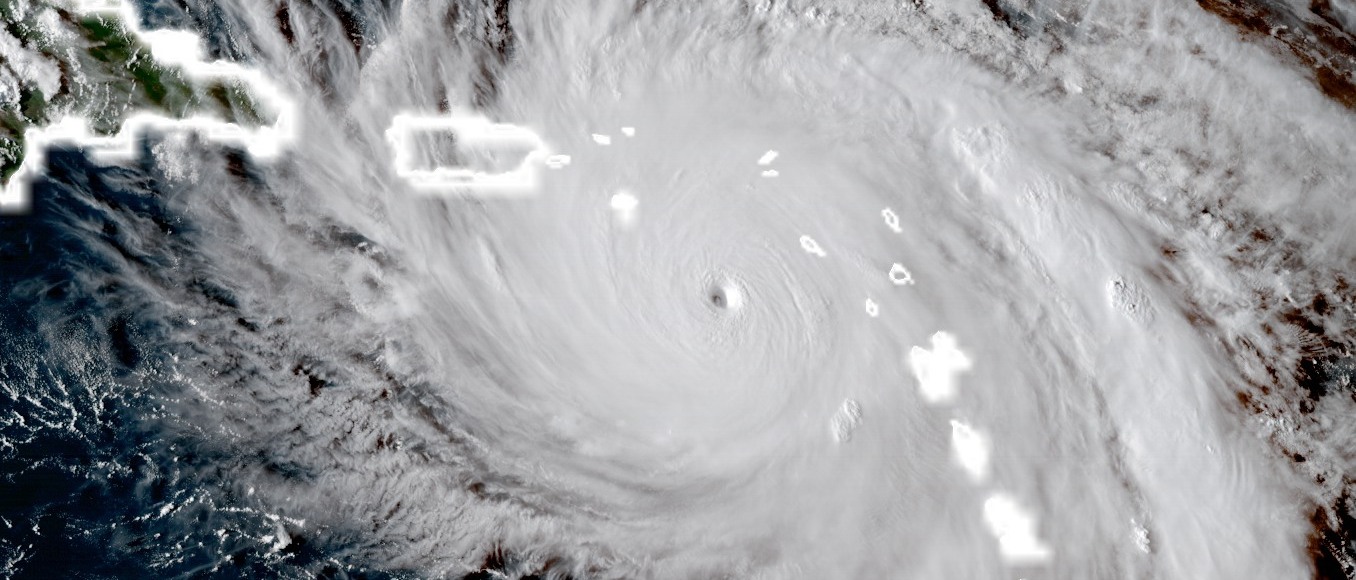

Much like New Orleans after Katrina and New York after Sandy — for readers outside the U.S., we can add Jalisco after Patricia, the Philippines after Haiyan and Meranti, Yemen after Chapala, Australia after Monica and Marcus, the list is so long — Puerto Rico after Irma and Maria has become an iconic example of climate’s wrath. But this small Caribbean island and U.S. territory of 3.3 million people is also something more.

Puerto Rico is now the latest island metaphor of the unthinkable, joining the likes of Maldives, Tuvalu and other vulnerable islands with a very particular message for the world.

It is a message carried passionately in UN climate talks by the Alliance of Small Island States, whose nearly 50 member countries and observer territories represent a combined population of 365 million, according to the organization’s website.

AOSIS, you’ll recall, was the chief driver in the 2015 Paris Climate Agreement behind the reduction of the temperature threshold from 2ºC to the safer 1.5ºC, with the “1.5 to Stay Alive” movement.

Well, 1.5ºC is not only closer today than even AOSIS pitched two years ago; the most serious voices now consider it unavoidable, and Puerto Rico shows us all just how high that takes the stakes for every island and coastal region.

While AOSIS pushes that front, islands are gaining priceless insights from the work of the entire global resilience ecosystem.

In Puerto Rico, that includes the work of the San Juan Resilience Office, part of the 100 Resilient Cities initiative of the Rockefeller Foundation, as well as the Resilient Puerto Rico Advisory Commission co-sponsored by Rockefeller, the Ford Foundation, and Open Society Foundations.

A local group has joined the Urban Resilience to Extremes Network, or UREx, created by Arizona State University, to conduct valuable practical research. Others are on board in multiple ways.

God knows we and every island can use all the insight we can get. Puerto Rico is small at 100×35 miles, smack on the path of the Atlantic hurricane corridor, with a mountainous terrain that impedes recovery efforts, an economy easily smashed by a significant storm, large pockets of low-income communities throughout, an aged infrastructure that will take capital we don’t have to fortify or rebuild, high dependence on food and supplies flown and shipped from around the world, and a level of corruption that gets in the way of the smartest allocation of relief and recovery funds. (Sounds familiar?)

The particulars differ, and climate events are handled with varying degrees of success from one island to another. But this is a story of fundamental vulnerabilities and the greater challenges facing, and awaiting, ocean-locked islands vs. land-rich continents where governments, people and companies have more options.

Every climate model indicates Puerto Rico won’t be as fortunate as we’ve been, with a decade or more between major hurricanes. They will likely come at us with greater frequency and fury, giving us precious little time to recover.

Add the occasional extended drought, on an island with precious little freshwater and no money to keep our reservoirs sediment free, plus the coming Age of Urban Heat, sure bouts with plagues and wildfires, and worsening sea-level rise, and the loudest possible alarm should be going off in every government agency, every corporate board room, every university classroom, and every family dining room. The same goes for every AOSIS member.

Today, resilience isn’t just a must. Resilience is everything.

Yet, those alarms are not yet heard. Not here, not in most places around the world. To be sure, Puerto Rico’s situation is worsened by the massive public-debt crisis that threw the island into the hands of a bankruptcy process and an austerity-driven federal oversight board.

The relevance to resilience is that it diverts the attention of government and private-sector leaders, and more importantly highlights our lack of resources to implement far-reaching resilience, knowing that federal recovery funding alone will not come close to what is needed. Prioritization of the spend is central, therefore, and figuring that out will be one of the top storylines of this TRJ Content Series.

Those are some of the obstacles in our way. Every island has its share. Ask the U.S. and British Virgin Islands, Dominica, Guadeloupe and others right near us hit just as hard by Irma and Maria, if not harder. Our series, again, will focus on Puerto Rico, but with the goal of applying the lessons to every AOSIS member and others who choose to listen.

So what are those lessons? What can every vulnerable island and coastal region do? What can we and others pick up from this experience, given the climate that is coming?

We posed those questions-of-the-moment to Craig Fugate, FEMA Administrator during both Obama terms, 2009-2017, and today Chief Emergency Management Officer at One Concern, a California-based firm that deploys advanced AI, machine learning and modeling to help places become more climate and earthquake resilient.

“This is going to be a critical time frame. For the first time, Puerto Rico will have tens of millions to hundreds of millions of dollars to invest in building resilience, but that’s not a lot of money when you look at all the needs, and it would be very easy to spread these projects out so much that we don’t really build the resilience we hope to.”

Craig Fugate interview

As you watch those magical 30 minutes, and since this is all about finding solutions, see how many priceless lessons you glean from his answers to guide the work going forward. Here are but three that will guide the content series:

1. Rebuild for future risks

STOP PREPARING FOR THE FUTURE BASED ON THE PAST. That is probably the principal holler of adaptation professionals today, including Fugate.

“How come we always use the last 100 years worth of weather data to figure out what the future’s going to look like?” he asks rhetorically. “The future is changing so fast, these events are happening so quickly, you’ve lost the meaning of the 100-year event. What if it’s a Harvey [next] and dumps 50 inches of rain on Puerto Rico?”

When rebuilding, he continued, “don’t just build back to the minimum standards. If you’re building back to Maria, you still may not be building back to what the future risk will be.”

In this recent TED Talk, Georgetown Climate Center Executive Director Vicki Arroyo called it the end of stationarity, or the delusion that extreme weather today follows the same pattern as decades past and allows you to still plan future development accordingly. Those patterns, she and Fugate say, are history.

“If we wait for the disasters, then it’s too slow, and we’re behind. We don’t have that luxury,” Fugate added. “If we’re not looking at what we’re rebuilding today against the future and we’re only looking at the past, then we have ensured that we’ll fail in that disaster when it happens.”

For the TRJ Puerto Rico Resilience Content Series, future risk is default. All else stems from that starting point.

2. Practice the new art of modeling

But with so much inherent uncertainty, how then are we supposed to plan?

Enter machine learning and artificial intelligence, today a booming industry across many fields of endeavor. In the case of climate change, it allows firms like One Concern to model and predict with high accuracy which properties, neighborhoods and critical infrastructure stand to suffer most from a natural disaster and which to prioritize in the rebuilding.

The technology fits seamlessly with the data-gathering Smart City sensors and nodes we wrote about earlier this month, across all 16 infrastructure, economic and social verticals.

Armed with that data, city authorities and private owners can prepare better, react faster, rescue more people, and safeguard more assets. The damage scans that for decades have taken months can now be done in minutes or hours.

“How do we look at the future when we don’t have any data?” Fugate asks. “Now we’re able to look not just at what happened in the past, but at what can happen in the future.”

That is today’s promising innovation, and One Concern and other firms are engaging authorities in Puerto Rico on this front.

The island, he suggests, “is not going to have enough funds to do everything, but we can start modeling what are the most vulnerable areas.”

Prior to the latest modeling technology, FEMA and city authorities only had a “project by project” way of weighing prevention, evacuations and rebuilding. “You couldn’t look at total impacts or at various scenarios.”

Today, they can focus on “how we can predict better what kind of impact that [event] is going to have, how can we reduce that risk and actually model out how this project will perform” under various scenarios, “and then look at that project in combination with other projects and see if we’re getting the best return on our investment.

“Not every project is going to give us the best return. We’ll have to be extremely targeted on what we do invest in. Are these projects really increasing our resilience score in the face of climate disruptions?”

3. Be ready for the inland move

That brings us to one particular future scenario, easily the toughest for most people, including our leaders in government, business, NGOs, the press and academia, even to envision, much less act upon.

But you know, failing to tackle this is no longer an option. It is now an inevitable part of the island life we love and treasure.

PTSD, or post-traumatic stress disorder, is common following a natural disaster and can render an entire community or population ineffective in the response. The growing field of disaster sociology is coming up with fascinating insights in this area.

In the island’s inability to pivot quickly toward greater resilience, signs of PTSD abound, which brings up the need to work on culture, both organizational at companies and government agencies, as well as socially and in the press. A mind shift beckons, in addition to smart modeling and wise funds allocation.

Then there’s pre-traumatic stress disorder, when a future catastrophic event triggers paralysis in taking remedial action now. Nothing provokes that reaction more than the sea-level rise happening already and sure to worsen sooner than previously expected, along with the storm surges that come with it.

The sea-level question today, Fugate says, is: “What areas can we harden, and where should we be looking to move?” With the modeling in hand, “now you have to start making decisions.”

That is worth repeating: “Now you have to start making decisions.” He continues: “It’s almost impossible to get people to move before the impacts. After something happens, let’s make sure we have the plan in place where we’re not going to build back to where it was, but we know where we’re going to build when we have that opportunity.”

In the new resilience lexicon, “some people call it strategic retreat, but I don’t like the term retreat. I think it’s managing our risks by moving inland so that we maximize the resilience and minimize the disruptions.”

Yes, it’s tough, but we really do have to face it

No matter what you call it, I say Amen. As a glance at this “drowning islands” Google search reveals, not only is this already the reality around the world, but we must stand inspired by those who overcome PTSD and face down ultimate consequences with great vision and valor. In our Content Series, w want to tell their stories, as well.

Early last year, months before Maria, I led a U.S. Green Building Council Puerto Rico Chapter resilience task force that explored precisely these scenarios. The group included some of Puerto Rico’s leading climate scientists, and even they found the result of their research hard to swallow.

Their hesitation to come out, tell the people, and create a culture of resilience, was and remains gut wrenching.

And yet, consider what we agreed is happening. In the coming decades, even as the island deals with the likely series of storm, flood and drought events that will hit us, Puerto Rico must begin to think of the unthinkable — those decisions Fugate rightly says we must start making: the relocation (retreat?) of the international airport, maritime ports, power plants, population centers, major highways, schools, hospitals, and the entire tourism zone stretching from Old San Juan to Isla Verde — not the colonial buildings and cobblestone streets physically, of course, but offer tourists another experience inland.

What will that Puerto Rico look like? This is not far off — the sea-level expert in our group guesstimated a one-meter rise as early as 2050, enough to drown the airport, sea port, convention center, most of Condado, and more — and we simply cannot allow ourselves to be pre-traumatized by that scenario.

It might take longer, but it might not. And in any case, we already know it’s coming for certain, so it is high time, and more so now that we have some federal dollars, to ask those vexing questions and make decisions. This Content Series seeks to provoke them, to force the issue, as it were.

The challenge of resilient jobs

Which of those assets can likely be salvaged? What will probably be lost? In the years between now and then, what are the climate impacts and scenarios we should focus on, the resilience investments we should prioritize? Which roads make sense to divert and lift, as New Orleans has done? Which coasts should we buffer, as Manhattan is doing? Which properties can float, as Denmark is building?

Even with these investments, will our people stay? Will new companies come and create jobs? What kind of economy will we have? When whole communities must relocate, will they choose inland or Florida?

Did I ask what kind of economy will we have? Now there’s a vulnerability to solve. If we’re seeing anything in Puerto Rico and across our neighboring archipelago six months after 9/20, it is the time and complexity involved in relifting a devastated island economy.

Smaller Caribbean and Pacific islands depend far more on tourism than we do, with a smaller land area to relocate airports, hotels and other economy-nourishing infrastructure, and therefore face higher future risks.

But as we’re seeing in Puerto Rico, more size and diversification has provided only partial consolation. Maria did catch us stuck in a lost decade of fiscal and economic contraction and made the recovery harder and longer. What we aim to do in the Content Series is sort things out — fiscal crisis and oversight board, local development plan, resilience vision and investments, where the money will come from, more — to help government and corporate leaders make decisions.

The big economy question for Puerto Rico and every vulnerable island is how to make our jobs and businesses resilient to multiple extreme weather events when we don’t have much time between impacts? We already know the employment base of an island is fragile. We’re certainly seeing that in Puerto Rico! So how can we create climate-resilient jobs to keep our people home?

And beyond our shores, how do we shield ourselves from supply-chain interruptions as climate change hits the places around the world that provide the 80-or-so-percent of the food and supplies we consume.

That, in a nutshell, is our Puerto Rico and Islands Project at TRJ. We aim to look beyond Irma and Maria, beyond the blurred and PTSD-provoking present, and peek into the future, to provide content that guides those tough but timely decisions.

Time is so short. The need is so upon us. I pray the answers we come up with in this Puerto Rico case study will make a significant difference, here and beyond our coasts. It’ll be our great honor.

Great article! I look forward to future information on mitigation plans for Puerto Rico and surrounding islands.

LikeLike

Thank you, Karen. As I say in the piece, we’ll be publishing a Content Series on resilience in Puerto Rico and the islands of the world, so by all means stay tuned!

LikeLike

Pingback: During our darkest moments, focus to see the light – The Resilience Journal

Pingback: Series of resilience-funding reports leave Puerto Rico naked, unless this man steps up – The Resilience Journal